Written by Michael Dijkstra on 14 Dec 2020

I hurried as quickly as I could. It was my final year chemistry test and I had to make sure I calculated the correct concentration or I would fail. As I hurried, I added too much of one chemical into the beaker. I knew as the last drop hit the beaker the result was going to be wrong but I continued anyway. It took 10 more minutes to finish the experiment and as predicted, the results were useless. I knew right there and then that I had to do it right or not at all.

The same applies for user stories. If you merely put something down because you have to, they become useless. You can’t use it, your team can’t use it and the whole point of doing it in the first place is lost.

The purpose of a user story is to help communicate the goal the user is trying to achieve.

The correct format for a user story is:

In order to [achieve a benefit]

As a [role]

I want [to perform an action]

To understand what makes a good user story, let’s first look at a bad user story:

In order to receive your newsletter

As a user

I want to subscribe to your newsletter.

Let’s break it down and see what’s wrong.

Firstly, describing the role as “a user” doesn’t add any value to the conversation. You have an opportunity to provide extra context by specifying a role such as visitor, admin or logged in user.

Secondly, you know a user story smells when you find you are repeating yourself. In this example, the goal of the user is also described as what they want to do.

When you think about it, does the visitor really want to subscribe to your newsletter or is there something more valuable?

In this situation, a good user story would be:

In order to never miss out on a special offer

As a visitor

I want to subscribe to the newsletter.

This user story now describes what the value for the user is, their role and you know what action they want to perform to achieve their goal.

By spending a moment figuring out what the user really wants, you’ve also penned your headline copy, “Never miss out on a special offer”, and your call to action, “Subscribe”.

The power of a good user story doesn’t stop there. You can also use your user story to drive the validation of your feature.

Using what you’ve already done you can say:

Hypothesis

We believe visitors never want to miss out on a special offer

Metric

This will be validated when 20/200 visitors subscribe

If you’re having trouble making sense of one of your user stories, let us know on Twitter.

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 18 Mar 2013

Just over one year ago I sat down and started building Storyberg with the aim to create a Lean Product Management tool. It began as a side project of mine and within a few months I started using it at Pollenizer. A few months later all the teams at Pollenizer dropped JIRA and started using Storyberg on a daily basis.

In December 2012, Kevin Nguyen joined Storyberg as a co-founder and helped secure initial investment from Startmate.

In January 2013 we both went full time. By that time, over 120 people had signed up, however the data showed that we were the only ones to validate our features. People signed up but were only using our tool for task management, not hypothesis validation.

We decided that we did not want to build another project management tool that’s got a better design/UI so we pivoted (for lack of a better word) to focus on the validation part of the lean startup workflow. We quickly relaunched our product as an analytics tool.

Our pitch was:

“Google Analytics tells you something happened, KISSmetrics tells you who did it, Storyberg tells you who did and why”

Over the next couple of months we learnt there was not enough value in the ‘why’ on it’s own, without all the extra stuff attached to the ‘who’ which services like KISSmetrics offers. At the time, we did not have the resources or desire to build all the baseline features of a product like KISSmetrics and then add our own unique value proposition on top.

It was time to make another tough call and we asked ourselves a lot of different questions. For example could we add something like a direct action onto the end of the analytics? No, this would provide the same product as services like Usercylce, Totango or Vero.

In the end, as a team, Kevin and I believed we had exhausted our possibilities with Storyberg and did not have anything else to firmly ‘pivot into’. The Lean Startup methodology is a process that requires discipline, and we can’t put a tool around this process. The solution to solve the problem we set out to tackle, ‘Help people validate they’re building something people want’, is an education play and this is not a direction we want to go in. The alternative would be a consulting play, but this isn’t going to build a scalable global business.

So today, we made our final call and we are closing down Storyberg.

Thanks to everyone for their support and in particular all the mentors from Startmate.

[Insert Sad Penguin]

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 28 Jan 2013

Cohorts are nothing new. Fred Wilson blogged that the cohort analysis is one of his firms favourite measurements back in October 2009.

“I’d encourage everyone doing a web startup to adopt the startup metrics methodology and within that methodology, make sure you are looking at cohorts of users, not just all of your users in the aggregate.” 1

The great benefit of cohorts is that they make it clear if user engagement is actually improving over time.

In most analytics tools cohorts are automatically created by week or month for the duration that metrics are recorded. This sounds great in theory because it’s easy to do from a programming perspective, but it rarely works in practice.

Given that a cohort is a group of people who share a common experience, they should be created when the experience for the user of an application changes, or in other words, when feature releases occur.

The benefit of release cohorts over generic weeks or months is that you can see if the product changes you are making are positively or negatively impacting user engagement over time.

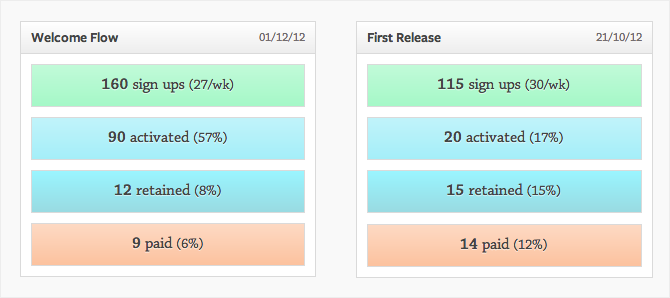

For example, say your previous release cohort shows that users are not activating, so you create a new welcome flow for your application. This is a significant release so you create a new cohort. Users start signing up to the app and activation has improved significantly. You pat yourselves on the back and mark that release off as “Validated”.

As time goes by, you continue to monitor and compare the two cohorts. While initial activation might be significantly better with the new welcome flow, the data shows retention is much worse, as is paying customers.

Therefore this welcome flow is not the golden feature you first thought it was and you now need to talk to users who signed up after you released it. Good thing they’re grouped together in a cohort.

Release cohorts are a new feature we implemented into Storyberg. Do you think they can help you validate you’re building something people want? Let us know on Twitter

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 27 Jan 2013

The cafe on the left really should be busier. They have friendly staff, music playing in the background and a place to sit while you wait. The cafe on right is filled with pretentious staff, there’s no music playing and you stand in the gutter while you wait. But they are packed. And it’s because of one thing: they make really good coffee.

When you want a coffee, you want the best coffee on offer. Nothing else matters.

Too often I see apps that do a number of different things and developers start to worry about insignificant features or button colours when what they should be doing is focusing on doing one thing really well.

The key activity of any app is the point where the app provides the most value to the user. Generally this is the exact point where their problem is solved, and the more often you can solve their problem, the more likely they will continue to use your app, pay for it, and tell their friends about it.

Finding your key activity isn’t as hard as it sounds. Here are some examples for inspiration to determine yours:

Value: Being more productive

Key metric: Closed tickets

If people close tickets they’re completing work to be done and being productive.

Value: Learning

Key metric: Videos watched

If people continue to watch videos it means they’re finding them valuable and most likely learning.

Value: Lead generation (for advertisers)

Key metric: Ad clicks (leads)

If people click on ads, advertisers get more leads and go on to buy more advertising.

Value: Having a question answered

Key metric: Answers

If people get answers to questions then they’ll ask more questions.

Value: Money in the bank

Key metric: Transactions

If users transact money it means they’re getting paid, and who doesn’t love that?

Value: Achievement

Key metric: Level up

When users level up they’re achieving something and they’ll be motivated to continue to achieve more.

Value: Revenue

Key metic: Sales

When a vendor frequently sells goods then they will keep their store open.

If you’re looking for raise money, or a reason to quit your day job, then nailing your one key activity will give you the confidence to take the leap and get investors to back you along the way.

What’s your one key activity? Let know us on Twitter.

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 12 Dec 2012

“Although the posts were unpaid, Josiah [Franklin] practiced the art, which his son would perfect, of marrying public virtue with private profit: he made money by selling candles to the night watchmen he oversaw.” 1

I have just started reading the Benjamin Franklin biography by Walter Isaacson (the same author who later wrote Steve Jobs biography) and the above quote really caught my attention because I feel it perfectly describes what we’re setting out to do with Storyberg.

We’re going to help startups all around the world build more successful businesses by knowing they’re building something people want. While we are building Storyberg and charging a monthly subscription, at the same time we are also going to help entrepreneurs by hosting office hours, events, workshops and giving back to the startup community as much as possible.

Essentially, we will be working, unpaid, to watch over the entrepreneurs while Storyberg is the tool they will use to get the job done.

I’m not sure of all the details, but I like to think that Josiah made high quality candles to make sure the watchmen he oversaw could do the best job possible. Regardless, that’s what we’re going to do.

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 09 Dec 2012

Last week, I felt like I was saying the same thing over and over again. And I was, because Storyberg was selected for the final interview day for Startmate.

After a quick focus talk from Pollenizer founder Mick Luibinskas, the 23 startups attending the day were allocated chairs around the room and the Startmate mentors would ask each startup why they should be chosen for the program. Each business had 10 minutes, one-on-one, to convince them to choose their startup.

Every interview began the same way:

“Let’s start with your one minute pitch”

Everyone you talk to about pitching says you need to get your elevator pitch down pat, and there’s no better way to do it than by repeating yourself 15 times in the one day.

After a full day of pitching, my tips for the crafting your one minute pitch are the following:

To bring it all together, here is our one minute pitch:

It doesn’t matter if your business is one day, one week or one year old, the best way to learn how to pitch is to pitch.

So … what’s your one minute pitch? Let know us on Twitter.

Written by Michael Dijkstra on 08 Dec 2012

Ideas are worthless without execution

Execution is worthless without traction

Traction is worthless without revenue

Revenue is worthless without profit

Credit to Bosco Tan who helped refine the above phrase and Simon Males who saved it in a gist.

Want to build a more successful startup by knowing you're building something people want? Start your story on Storyberg.

© Storyberg